Case 1 170825-1 (S1705220)

Conference Coordinator: Sarah Stevens

//

Adult, female, quarter horse..

The mare had exhibited signs of ataxia, proprioceptive deficits and then died within a 72 hour time period.

The mare was acquired approximately 60 days prior to death for breeding purposes. She was vaccinated almost a year prior for non-specified.

Presented for hindlimb lameness, which was determined to be ataxia and neurologic deficits on physical examination.

The mare almost fell over when the veterinarian attempted to lift a hind limb. Proprioceptive defects were present in all four limbs (hind > fore).

There were no cranial nerve deficits, mild intermittent muscle fasciculations, particularly of the shoulder and gluteal muscles, with abnormal sweating over flank and gluteal region.

These signs progressed over the next two to three days to the point the mare could barely get up and then could only stand for a few minutes at a time before going back down, often falling down and progressed to death.

The necropsy of a 429.2 kg buckskin quarter horse mare with no markings, began at 12:05 pm on Saturday July 22, 2017.

The body condition was good, with adequate fat deposits and muscle development.

The carcass was in moderate post mortem condition based on degree of autolysis .

The ocular and gingival mucosae were slightly pale.

The subcutis of the right frontal area of the head had edema and hematomas.

The trachea was filled with ret-tinged stable foam.

The lungs were diffusely red and wet with occasional petechial hemorrhages along the visceral pleura.

The myocardium was slightly pale and the pericardium contained red-tinged fluid.

The liver was slightly pale with a prominent reticular pattern.

The stomach contained small amounts of dark brown to red fluid.

The mucosa of the gastric fundus had numerous 0.2 to 0.6 cm in diameter irregular ulcers.

A few nematodes were identified in the small intestine, morphology consistent withParascaris sp.

The cecal and colonic contents were within normal limits, with the exception of the presence of a 15 x 10 x 9 cm enterolith within the lumen of the right dorsal colon.

Kidneys were within normal limits.

The urinary bladder contained small amounts of sand-like yellow material.

The brain and spinal cord were completely removed and analyzed with no identified significant abnormalities.

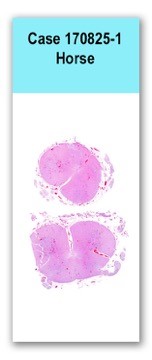

This slide has two sections of spinal cord, in which there are moderate to marked inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells and occasional macrophages expanding the Virchow- Robbins space.The neuropil of the gray matter is moderately hypercellular (gliosis) with occasional neuronal degeneration and necrosis, multifocal hemorrhages and axonal swelling and degeneration (spheroids).The white matter has multifocal, mild axonal degeneration and few, scattered digestion chambers.

West Nile Virus: Positive immunoreactivity in occasional axons.

Spinal Cord (distal cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral): moderate to severe, lymphoplasmacytic myelitis (mostly poliomyelitis) with neuronal degeneration and necrosis, spheroids, gliosis and hemorrhage

PCR: Positive for West Nile virus

PCR: Negative for Eastern and Western equine encephalitis, equine herpesvirus (1 and 4)

Rabies: Negative

IHC: Negative for Sarcocystis sp.

IHC: Positive for West Nile virus

West Nile Virus (WNV) is a flavivirus that is mosquito borne and maintained via a bird-mosquito-bird cycle.

WNV in birds can develop a prolonged and severe viremia with widespread virus distribution in many organs.

This is in contrast to WNV infection in horses where viral antigen is sparse and may be limited primarily to the central nervous system.

This was a good example of WNV in a horse as there were classic lesions and less subtle than in many equine WNV cases. Gross lesions, as in this case, are often absent.

Histologically, WNV tends to mainly affect the brainstem and thoracolumbar spinal cord with the cerebral cortex, cervical spinal cord and cerebellum less likely affected.

Furthermore, lesions tend to be more gray matter oriented. Changes include encephalomyelitis, gliosis and glial nodule formation with variable degrees of neuronal degeneration and necrosis.

In subtle cases, lesions can be mild and restricted to only thin inflammatory perivascular cuffs of occasional blood vessels.

This, again, is in contrast to avian cases where there are extraneural tissues affected, such as the heart and liver.

Diagnosis relies on clinical signs, histology, PCR and immunohistochemistry.

In this case, PCR and immunohistochemistry were confirmatory as well as ruling out other etiologies or co-diseases such as rabies, Eastern or Western equine encephalitis and herpesvirus.

WNV was considered most likely in the course of the discussion due to the history of brainstem and spinal cord predominant lesions as well as targeting of the gray matter.

In humans, zygomycoses tend to affect immunodeficient patients, but some species can cause infections in the immunocompetent, most often in traumatized tissues.

Cantile C., Del Piero F., Di Guardo G and Arispici M. Pathologic and immunohistochemical findings in naturally occurring West Nile virus infection in horses. Vet Path. 2001. 38:414-421.

Toplu N, Oguzoglu TC, Ural K, Epikmen ET, et al. West Nile virus infection in horses: detection by immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and ELISA. Vet Path. 2015. 52(6):1073-1076.